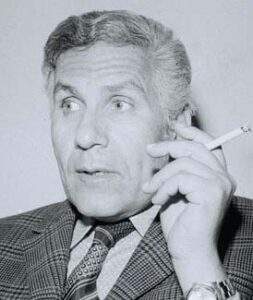

Yusuf Idris | A Tray from Heaven | An Analytical Study

–Menonim Menonimus

Yusuf Idris | A Tray from Heaven | An Analytical Study

Yusuf Idris | A Tray from Heaven | An Analytical Study

‘A Tray from Heaven’ is a Greek Arabic short story written by Yusuf Idris (1927-91) a Greek novelist, story-teller, essayist, journalist and critic. The story has no plot but only characterization. Social prejudice is the main theme of the story.

The author has given a detailed account of prejudice that prevailed even in twentieth century Egypt as follows:

Like other towns, Munyat al-Nasr (a town in Egypt) was superstitious about Friday, and any event that took place on that day was viewed as a sure catastrophe. The people of the village were, however, excessively superstitious. They were opposed to any work being done on that day for fear it would end in failure, and thus they postponed all work until Saturday. If you asked them why they were so superstitious about it, they would tell you it was because Friday is a day of misfortune. It was, however, clear that this was not the real reason; rather, it was merely a pretext enabling the farmers to put off Friday work until Saturday. And so, Friday became the day of rest. The word ‘rest’ was considered ugly among the farmers, as well as an insult to their toughness and to their extraordinary ability to work indefatigably. Only townspeople needed rest, that is, those who had fresh meat and worked in the comfort of the shade, and in spite of that, still ran out of breath. Weekly rest was a heresy. So, Friday must surely have been a day of bad luck. As a result, work had to be postponed until Saturday.

There are some characters in the story most of which are naïve and unlettered. Among the characters, a man named Sheik Ali is the main character who has occupied much space of delineation in the story. The author has portrayed him as an extraordinary individual character in the story with whimsical traits. The author has written about him as follows: In fact, he himself was regarded as a joke. His head was the size of a donkey’s, whereas his eyes were as wide and round as those of an owl, except that he had bloodshot in the corners. His voice was hoarse and loud, like a rusty steam engine. He never smiled. When he was happy, which was rare, he would laugh boisterously. When he was not happy, he would scowl. A single word that he did not like was enough to make his blood boil to the extent that it would be turned into fuel, and he would swoop down on the one who had uttered the word that had caused offense. He might even bear down on this person with his fat-fingered hands, or his hooked, iron-tipped stick, which was made out of thick cane. He was very fond of it and cherished it, calling it “the commandant”.

Sheikh Ali’s father had sent him to al-Azhar for his education. One day, his teacher made the mistake of calling him “a donkey”, to which Sheikh Ali, true to type, had retorted: “And you are as stupid as sixty donkeys.” After he was expelled, he returned to Munyat al-Nasr, where he became a preacher and imam at the mosque.

One day he mistakenly performed the prayers with three genuflections. When the congregation attempted to warn him, he cursed all their fathers, gave up being an imam and stopped going to the mosque. He even gave up praying. Instead, he took up playing cards and continued to play until he had to sell everything he owned. At that moment, he swore he would give that up too.

When Muhammad Effendi, the primary school teacher in the district capital, opened a grocery shop in the village, he suggested to Sheikh Ali that he should keep the shop open in the morning, which he accepted. However, this only lasted for three days. On the fourth day, Muhammad Effendi could be seen standing in front of his shop, dripping with halva‘ Sheikh Ali had discovered that Muhammad Effendi had put a piece of metal in the scales to doctor them. Sheikh Ali had told him: “You’re a crook.” No sooner had Muhammad Effendi said: “How dare you, Sheikh Ali! Shut up if you want to keep your ‘oh!’ then the sheikh hurled a handful of halva at him. From that day onwards, nobody ever dared to give Sheikh Ali any work. But even if anybody had dared, it would not have mattered as Sheikh Ali himself was no longer interested in working anyway. Sheikh Ali was also a very ugly man as well as irascible and unemployed, and yet nobody in the village really hated him.

Quite the contra; most of the villagers loved him and liked to exchange funny stories about him. Their greatest joy was to sit around him and arouse his anger, much to everyone’s merriment. When he got angry and his features darkened, unable to speak, it was impossible for any of the bystanders to control themselves and not collapse with laughter. They kept on egging him on, while he grew angrier and angrier. They would laugh until the end of the gathering. Everyone would utter: “What a character you are. Sheikh Ali!” They would then leave him alone to vent his anger on “Abu Ahmad”, which is what he called his poverty. He considered Abu Ahmad his archenemy. Sheikh Ali spoke about his poverty as if it were a person of flesh and blood standing in front of him. Usually, the tirade would be sparked if someone asked him: “So what has Abu Ahmad done to you today, Sheikh Ali?” Sheikh Ali would fly into a real rage at that moment because he did not like anyone to talk about his poverty when he was talking to it. And whenever people talked about his poverty he would be driven to rage. Sheikh Ali was, in fact, quite shy, despite his stern features and words. He preferred to go for days without smoking, rather than ask any of the villagers to roll him a cigarette. He always carried a needle and thread about his person in order to mend his jilbab in case it became torn. When his clothes got dirty, he would go far away from the village in order to wash them and would remain naked until they were dry. Because of this, his turban was cleaner than any other turban in the village. It was only natural that the people of Munyat al-Nasr laughed at this new drollery on that particular day. However, in this case, the laughter soon died down and people fell silent, tongue-tied with fear. The word blasphemy was a terrible one to use, especially in a village that, like any other, lived in peace and tranquillity. Its people were good people, who knew nothing except their work and family. Just like any other village, there were petty thieves stealing corncobs, big thieves raiding cattle pens and snatching the excess cattle with hooks; big and small tradesmen; known and unknown loose women; honest folk and liars; spies; sick people; spinsters and righteous people.

However, you found them all in the mosque when the muezzin called the faithful to prayer. You would not find a single one of them breaking their fast during Ramadan.

He seems to be an eccentric rounding whom the people of the town makes jokes and derive merriment. The author portrays his eccentricity as follows:

Sheikh Ali’s head was bare, and his short-cropped white hair glistened with sweat. In his right hand, he clutched his stick. His eyes were glowing like embers, while a look of fierce and senseless anger had settled on his face. He said, addressing the sky: “What do you want from me? Can you tell me what is it that you want from me? I left al-Azhar because of some sheiks who act as if they are the sole guardians of the faith. I divorced my wife, sold my house, and out of all the people you chose me to inflict Abu Ahmad on. Why me? Who don’t you send down your anger, oh Lord, on Churchill or on Eisenhower? Or is it because you can only do it to me? What do you want from me now? “So many times in the past you made me hungry, and I endured it. would tell myself: ‘Imagine it’s the month of Ramadan, and you’re fasting. It’s only one day, and it’ll pass.” But, this time, I haven’t eaten anything since yesterday afternoon, and I haven’t had any cigarettes for a week. I haven’t touched hash for ten days. And you’re telling me that in Paradise there is honey, fruit and rivers of milk, yet you don’t give me any of it! Why? Are you waiting for me to die of hunger? Why don’t you send him to America? Is he my destiny? Why do you torture me? I have nothing, except this gallabiyya and this stick. What do you want from me? You either feed me right now or take me now! Are you going to feed me, or not?” As Sheikh Ali uttered these words he was in a state of extreme fury; he actually began to froth at the mouth and became soaked with sweat, while his voice filled with fierce hatred. The people of Munyat al-Nasr stood motionless, their hearts almost frozen with fear. They were afraid that Sheikh Ali would continue and become blasphemous. But that was not the only thing that scared them. The words spoken by Sheikh Ali were dangerous … they would cause the wrath of God the Almighty, and it would be their village that would pay the price when His vengeance struck everything they owned. Sheikh Ali’s words threatened the safety of the entire village, and so he had to be shut up. In order to do this, some of the village elders began shouting placatory remarks from afar with a view to making Sheikh Ali regain his senses and hold his tongue. For a while, Sheikh Ali turned away from the sky and directed his gaze toward the onlookers: ….. Should he quiet until I die of hunger? Why should á keep quiet? Are you afraid of your houses, women and fields? It is only those who have something to lose that are afraid! As for me, I don’t have anything to be scared of. And if He is annoyed with me, let Him take me! In the name of my religion and all things holy, if someone were to come and take me, even if it was Azrael, the Angel of Death, himself. I’d bash his skull in with my stick. I’ll not be silent unless He sends me a table laden with food from heaven, right now. I’m not worth less than Maryam, who was only a woman after all, but I’m a man. And she wasn’t poor. I, on the other hand, I’ve had to suffer at the hands of Abu Ahmad. By my religion and everything I hold dear, I’ll not be quiet until He sends me a dining table right now!”

The sheikh once again turned to the sky: “Send it to me right now, otherwise I’ll say whatever’s on my mind. A dining table, right now! Two chickens, a dish of honey and a pile of hot bread – only if it’s hot – and don’t you dare forget the salad! I’ll count up to ten. And if the dining table’s not sent down, I’ll not stop at anything.” Sheikh Ali began to count, and the people of Munyat al-Nasr silently counted ahead of him, but they became increasingly nervous. Sheikh Ali had to be stopped. One of them suggested they get the strongest youths of the village to throw him to the ground, gag him and give him a thrashing he would not forget. However, one look at Sheikh Ali’s fiery, rage-filled, mad eyes was enough to forget the proposal. It would be impossible to knock Sheikh Ali down before he lashed out once or twice with his stick. Every youth was afraid he would be the one to be struck, and that instead of Azrael’s head being splattered, it would be one of theirs. For this reason, the proposal foundered. One of them said, impatiently: “You have been hungry all your life, man, why pick today?”

Sheikh Ali’s fiery gaze bored down at him, as he replied: “This time, Abd al-Jawwad, you weakling, my hunger has lasted longer.” Somebody else shrieked: “Alright then, man, if you were hungry, why didn’t you tell us? We would have fed you instead of listening to your nonsense!” Sheikh Ali then set upon him: “Me, ask you something? Am 1 going to beg to you, a village of starving beggars? You’re staging more than I am! Begjo? 1 have come to ask Him, and if He doesn’t give it to me. I’ll know what to do! Abd al-Jawwad said: “Why didn’t you work so that you could’ve fed yourself, you wretch?” At that point, Sheikh Ali’s anger reached its peak. He flew into a temper, quivering and quaking, alternately directing his harangue towards the crowd gathered at a distance, and at the sky: “What’s it to do with you, Abd al-Jawwad, son of Sitt Abuha?! I’m not working! 1 don’t want to work! 1 don’t know how to work. I’ve not found work. Is what you do work, you bovine part?! The work that you do is donkey’s work, and I’m not a donkey! I can’t bust my back all day longº I can’t hang around on the field like cattle, you animals. To hell with all of you! I’m not going to work! By God, if I was meant to die of hunger, I still wouldn’t do the work that you do! Never!”

In spite of the sheikh’s anger and the terrifying nature of the situation, people started laughing. The sheikh was shaking, and said: “Ha! … I’ll count to ten and, by God, if I don’t get a dining table, I’ll curse God and do the unspeakable.” It was clear that Sheikh Ali was not going to change his mind, and that he intended to go ahead with his intentions, which would have unimaginable consequences. As Sheikh Ali started to count, droplets of sweat poured down people’s foreheads, and the noon heat became intolerable.

Some started to whisper that the vengeance of God had begun to unfold itself and that this terrible heat was but the beginning of a terrible conflagration, which would consume all the wheat and crops. One of them made the mistake of saying: “Why don’t any of you get him a morsel of food, so he’ll come down?” Although Sheikh Ali was counting loudly, he heard these words and turned around, towards the gathering: “What morsel, you louts? A piece of your rotten bread and stale cheese that has all been eaten by worms? You call that food? I’ll only be quiet if a dining table arrives here, with two chickens on it.” There was a lot of grumbling in the crowd. Suddenly, one of the female bystanders said: “I’ve got a nice okra stewº I’ll bring you a plate of it.” Sheikh Ali shouted at her: “Shut up, woman! What’s this okra nonsense, you…! Your brains are like okra, and the smell of this village is like that of acid okra!” Then Abu Sirhan said: “We’ve got some fresh fish, Sheikh Ali, which we’ve just bought from Ahmad the Fisherman.” Sheikh Ali roared: “What’s this minuscule fish of yours, you bunch of minions! Do you call that a fish? Damn it, if He doesn’t send me two chickens and the other things I ordered, I’ll continue cursing – and hang the consequences!” The situation became unbearable. It was a question of either.

remaining silent and losing the village and everyone in it, or shutting up Sheikh Ali by any means possible. A hundred people called out to invite him for lunch, but he refused each time.

Eventually, he said: “I can’t continue with this poverty, people. For three days, no one has offered me even a morsel. So, leave off with the invitations now. I won’t shut up until you give me a dining table full of food sent by the good Lord.”

Heads turned around to inquire who had cooked that day, as not everyone cooked daily; indeed, it would have been highly unlikely for anyone to have meat or chicken. Finally, at Abd al-Rahman’s house, they found a plate of boiled veal, and they took it to Sheikh Ali on a tray together with some radishes, two loaves of crisp bread and onions. They told the sheikh: “Is that enough for you?” Sheikh Ali’s eyes alternated between the sky and the tray; when he looked at the sky his eyes gleamed with fire, whereas every time he looked at the tray his anger grew. The onlookers stood by in silence. Eventually, Sheikh Ali said: “All along I wanted a dining table full of food, you useless lot, and you bring me a tray? And where’s the packet of cigarettes?” One of the villagers gave him a packet of cigarettes. He stuck out his hand and took a large piece of the meat. He wolfed it down, and said: “And where’s the hash?”

They told him: “How dare you? That’s rich!” Indignantly, Sheikh Ali said: “Right, that’s it!” Then, he left the food, took off his jilb a band turban and once again started brandishing his stick, threatening that he would start blaspheming again. He would not be silent until they brought him Mandur the hash dealer to give him a lump of hashish.

Mandur said: “Take it. Take it, Sheikh, you deserve it! We didn’t see, we didn’t know you’d be embarrassed to ask. People sit with you and they seem happy, but then afterward they’re not interested anymore and leave you. We have to see to your comfort, Sheikh. This is our village, and without you and Abu Ahmad, it would be worthless. You make us laugh, and we have to feed you … What do you say to this?” Sheikh Ali again launched into a raging fury, at the height of which he lunged at Mandur, shaking his stick at him and almost hitting him over the head with it. “Laughing at me? What is so funny about me, Mandur, you donkey brain? Damn you, and your father!”

Mandur was running in front of Sheikh Ali, laughing. The bystanders were watching the chase, laughing. Even when the sheikh came after all of them, reviling and cursing them, they kept on laughing. Sheikh Ali remained in Munyat al-Nasr, and things still happened to him every day. He was still short-tempered, and people continued to laugh at his bouts of anger. However, from that day on they made allowances for him. When they saw him standing in the middle of the threshing floor, taking off his jilb and turban, grabbing hold of his stick and starting to shake it at the sky, they understood that they had been oblivious to his problem, and had left Abu Ahmad alone with him for longer than was necessary. Before a single blasphemous word left his mouth, a tray would be brought to him with everything he asked for. Occasionally, he would accept his lot, with resignation.

Thus the author Yusuf Idris has created an unparalleled character like Sheik Ali with so a funny, foolish, and crazy mentality that there can hardly be found a second one in the whole range of Arabic fiction.

The story is written in the third person with meticulous observance that substantiates the author how devoted he was as a writer.

The story has no construction as it bears no plot. The opening of the story is abrupt and full of curiosity as:

If you see someone running along the streets of Munyat al-Nasr, that is an event. People rarely run there. Indeed, why should anybody run in a village where nothing happens to warrant running? Meetings are not measured in minutes and seconds. The train moves as slowly as the sun. There is a train when it rises, one when it reaches its zenith and another one at sunset. There is no noise that gets on one’s nerves or causes one to be in a hurry. Everything moves slowly there, and there is never any need for speed or haste. As the saying goes: “The Devil takes a hand in what is done in haste.”

If you see someone running in Munyat al-Nasr, that is an event, just as when you hear a police siren you imagine that something exciting must have happened. How wonderful it is for something exciting to happen in such a peaceful and lethargic village! On that particular Friday, it was not just one person who was running in Munyat al-Nasr; rather, it was a whole crowd. Yet no one knew why. The streets and alleys were basking in the usual calm and tranquillity that descended upon the village after the Friday noon prayers when the streets were sprinkled with frothy rose-scented water smelling of cheap soap; when the women were busy inside the houses preparing lunch and the men were loitering outside until it was time to eat. On that particular day, the peace and tranquillity were broken by two big, hairy legs running along the street and shaking the houses. As the runner passed a group sitting outside a house, he did not fail to greet them. The men returned the greeting and tried to ask him why he was running, but before they could do so he had already moved on. They wanted to know the reason, but, of course, were unable to find out. Their desire to know compelled them to start walking. Then one of them suggested they walk faster, and suddenly they found themselves running. They were not amiss in greeting the various groups sitting outside the houses who, in turn, also started running.

However obscure the motive, it was bound to be known in the end, just as it is inevitable that people quickly start gathering at the scene of an accident. It is a small village. There are thousands of people who will give you directions. You are able to run its length and breadth without running out of breath. It did not take long before a crowd began to gather near the threshing floor. Everyone who was able to run had arrived; only the old and aged remained scattered in the street. They preferred to saunter, as village elders do, and to leave a space between them and the youngsters. However, they were also hurling, intent on arriving before it was too late and the incident became news.

The author has expressed his philosophy of life indirectly that some people take birth with exceptional unusuality.

The language of the story is simple, evocative, direct and fully expressive. There are some sentences that may be read as proverbs as:

“If you see someone running along the streets of Munyat al-Nasr, that is an event.”

“The Devil takes a hand in what is done in haste.”

There are similes that have enriched the language of the story as:

‘The train moves as slowly as the sun.’

The short story is of ideal length as it is written in not more than two thousand words.

To conclude it may be said that the story entitled, ‘A Tray from Heaven’ by Yusuf Idrish is a short story of character written in ideal length dealing with the theme of prejudice that has portrayed an unprecedented character like Sheik Ali with the trait of extraordinary individuality. 0 0 0

A Tray from Heaven

Read More: Izz al-din al-Madani Short Story ‘The Tale of the Lamp’-An Analytical Study

A Tray from Heaven

N. B. This article entitled ‘Yusuf Idris | A Tray from Heaven | An Analytical Study’ originally belongs to the book ‘Analytical Studies of Some Arabic Short Stories‘ by Menonim Menonimus. A Tray from Heaven

Books of Literary Criticism by M. Menonimus:

- World Short Story Criticism

- World Poetry Criticism

- World Drama Criticism

- World Novel Criticism

- World Essay Criticism

- Indian English Poetry Criticism

- Indian English Poets and Poetry Chief Features

- Emily Dickinson’s Poetry-A Thematic Study

- Walt Whitman’s Poetry-A Thematic Study

- Critical Essays on English Poetry

- Tawfiq al-Hakim’s Novel: Return of the Spirit-An Analytical Study

- Tawfiq al-Hakim’s Novel: ‘Yawmiyyat Naib Fil Arayaf’-An Analytical Study

- Analytical Studies of Some Arabic Short Stories

- A Brief History of Arabic Literature: Pre-Islamic Period …

Related Searches:

- A Tray from Heaven

- Layla al-Uthman

- Night of Torment by Laila al-Uthman

- Excerpt from the Egyptian Book of the Dead

- Notes on ‘The Doum Tree of Wad Hamid’

- Arabic Short Stories Archives

- Modern Arabic Literature